Hey – Is the world doing okay?

Silly question I know, but take a moment to answer it for yourself. Are things getting better or worse for people in the world? How do we know? I bump into the myth of Progress every now and again – the idea that things are the best they’ve been, that this is the golden age of humanity. I call it a myth, because while it’s usually told as fact, it’s really just a narrative. History is Storytelling, and historians a kind of storyteller. But unlike stories told for entertainment, history is storytelling with a purpose: stories of the past which inform how we understand today, and shape what we do tomorrow. The default view of history we are raised on exists to justify the status quo of power, convince us this is about as good as it gets and to not ask for more. Don’t buy it. Don’t let the storyteller convince you he isn’t there.

There is no singular “past”, or a single narrative of history. Every account of the past only considers some factors, definitions, or events, while seeing others as irrelevant. When we look into the vast, sprawling chronicle of all that’s come before, we make sense of it by locking onto certain pieces, crafting narratives, and in doing so always leave things behind. There’s single, unifying “past” which covers everything, but it’s in the multitude of our shared stories that we find history. We need to treat history like it is: narratives about what has come before which shape how we think about today, and what we think should be done tomorrow.

In my own life, I’d say the Myth of Progress is the most common narrative of history I encounter. It paints human history as violent, blood-soaked, anti-intellectual, anti-democracy, full of fools and con-men playing on the fear and vulnerability of starving masses to get loyalty and money. History which is full of cruelty, executions, torture, genocide, hunger, and ugliness in every sense of the word. Were these things present in history? Sure, I expect so, but this telling tends to put intention and agency on people long dead whose inner lives we can’t know. No history can give an objective view on the past, or accurately tell the human story, but they are all told with purpose. So this classical history of Progress: what’s the purpose behind it? What is gained, lost, and covered in using it? This telling of history covers the atrocities of our time, dislocating the darkness around us and pretending it doesn’t belong here. It whitewashes our shame.

A simple example: think on the Abu Ghraib prison scandal.

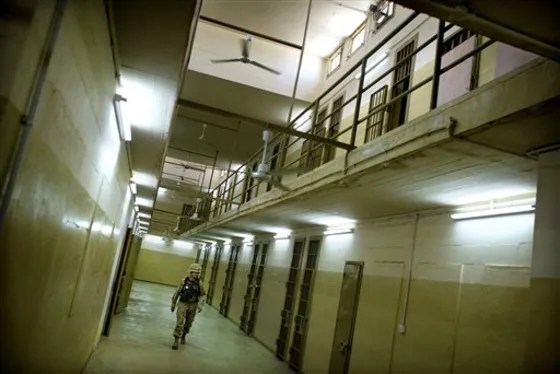

The Prison in 2004. Source: https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna26547591.

Early in the Iraq war (2003-2011), the United States Military and Intelligence services operated Abu Ghraib prison, near Baghdad, during their occupation of Iraq following the 2003 invasion. At its peak, the prison housed seven to eight thousands detainees, and a number of them were abused. Detainees were tortured, assaulted, physically and mentally abused, and at least one was killed, his body then desecrated. The Red Cross would determine that most of the detainees at Abu Ghraib were civilians with no links to armed groups fighting the US occupation. The details of the abuse, which was photographed, are sickening and disturbing, and appeared to have been not isolated cases but indicative of US policy (as far as the “torture memos” prepared before the invasion would suggest). What should we call this scandal? “Barbarous,” “medieval,” at odds with modern civilisation and human rights? Well, it was in violation of the principles established by the UN. But was it at odds with modernity?

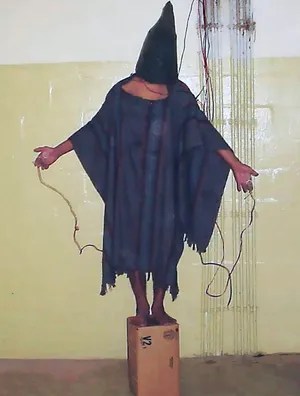

Almost every aspect of the Abu Ghraib scandal is profoundly modern.

The United States and Iraq are young nation-states, and the city of Abu Ghraib was built in the 20th century. The military occupation of Iraq by the US military across the Atlantic Ocean was a form of power projection which would have been impossible a few centuries ago, the prison system itself is a creation of recent centuries, and this specific prison was built in the 1960s. The planes that flew detainees around the globe to black sites didn’t exist until the past century, nor did the cameras which took evidence of the abuse. Even some torture methods (such as the famously photographed electrical shock torture) couldn’t have been done until the advent of electrical power. Abu Ghraib is a fundamentally modern atrocity, not in conflict with the modern civilisation but dependent on it. So why do we refuse to see the modernity of abuses like Abu Grhaib? Why do we paint ‘the past’ as bloody, ignorant, and cruel?

This was done by the ‘civilised.’ Source: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Abu-Ghraib-prison.

Because it makes our violence, ignorance, and cruelty an aberration, a mistake rather than a deliberate manifestation of power and control. When we paint the past as blood-soaked, ignorant, dirty, and ugly, we place those concepts on one side of the story, ‘the past’, and remove them from our current reality. It lets us tell a story of today in which these problems are solved, or almost solved: perhaps some ‘backward’ holdouts live like that, but not the good, ‘civilised’ folk. Of course, ‘civilised’ usually means Western – even though, at Abu Ghraib, it was a Western power doing the abuse. Categorising a people, be it Muslims or Indigenous peoples or people of the Global South, as ‘backward’ and ‘barbarous’ dehumanises them, legitimising exploitation and dispossession. A favourite trick in the Colonial and imperial textbook.

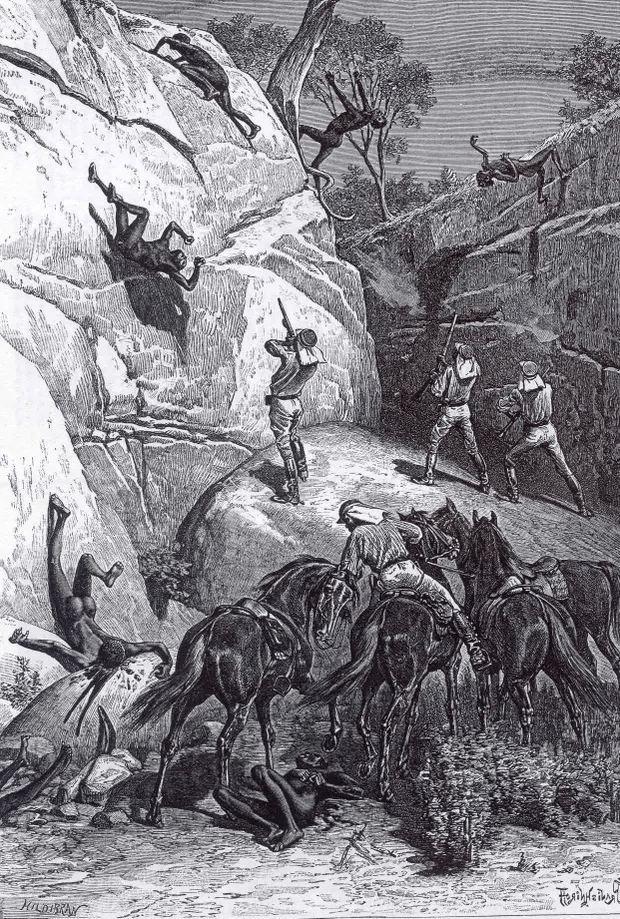

How about the Flat Earth conspiracy: humanity has generally understood the earth to be round for a long, long time, arguably since antiquity. Flat Earth is a modern conspiracy based on errors and manipulation, something with little if any historical precedence – similar things can be said of anti-vaccine conspiracies. If the people of the past were all superstitious morons, then our conspiracies seem quaint and a little embarrassing, rather than a shocking social development as we’ve become cynical and dismissive of expertise. If the violence of superstition is contained within the past, then the racist and imperialist sentiments of modern thinkers look accidental, rather than a predictable development from a worldview that presumes almost all non-white culture to be ‘backward’ and ‘primitive.’

White Settlers hunting First Nations Australians; one of many cases of colonial, and genocidal, violence in recent centuries. Source: Nathan Sentance, Australian Museum, https://australian.museum/learn/first-nations/genocide-in-australia/.

We need to challenge this narrative of history, because to most of our eyes, the reality is no, things are not going well. Some people are thriving, but multitudes exist in misery. There are decades, centuries old injustices that have never been reckoned with, some of them barely acknowledged. If before most of us were impoverished from lack of resources, now many are impoverished so that others can be comfortable. If we accept this is the best the world has been, we will make exploitation and violence tolerable. We become unable to see the cruel side of the world, or to meaningfully confront it. To recognise that cruelty, we need a different kind of history, one which doesn’t simply seek to validate modernity as the superior form of being. History is storytelling, and it is up to us to decide which story we think is most compelling, meaningful, and relevant to our lives.

There is no single ‘past.’ The default history we hear is the history of the West, as the West would like to remember it. Other views of history are possible. There is a history which argues that the past five hundred years of colonialism, globalisation, and innovation have built a machine of global iniquity, in which capitalism and imperialism combine to ensure the wealthiest and most powerful prosper, no matter the cost to everyone else. Our world is facing climate catastrophe and ecological disaster, and it seems utterly incomprehensible that world leaders are inactive in the face of it. Let this historical narrative answer that question for you: the world leaders don’t act because they don’t care – the political system we have built is made to protect the global powers over other nations, and those powers’ most powerful over their common citizens. Why would the powerful care if the world burns down if they continue to prosper through it?

I don’t want you to feel hopeless or disempowered. Cynicism is surrender, and what you and I both need to do is remember. Remember that history is storytelling, a narrative with intent. We need to give a different account, one which sheds light on the things Power and Empire want us to forget, one which empowers our resistance, defiance, and persistence. This narrative of history is leading our planet towards inaction in the face of complete, multifaceted catastrophe. We must listen to the voices of the voiceless, the people of the Global South and the dispossessed, and align ourselves with them. The current story tells us that the world has been getting better and more humane of late, that all we need to do is trust the system even as it destroys our world. Perhaps we can start hearing and sharing a different story.