You ever watch much Monty Python? I watched it sometimes growing up. In Life of Brian, there’s a scene of Judean rebels who want to drive out the Romans. Why? Because “what have the Romans ever done for us?” It’s spoken as a criticism, but it unravels as people list all the good things Rome brought; clean water, sanitation, good roads, medical advances, better education, even law and order. The joke is that for all their bluster and anger, these rebels have a lot to be thankful for: there’s a lot of benefits they like about the empire. I do like Monty Python, but I don’t think I can really enjoy this joke. Because underneath the whimsy and silliness, it’s a jab at the people who resist empire. The premise is that actually, empires can be pretty good. And that’s just propaganda.

I only realised this year that I didn’t even know the definition of what makes an empire. Do you know what it is? Put simply, an empire is a collection of countries or realms under one monarch or state. But that language is dry and doesn’t get to the heart of what’s wrong with empire. Another way to explain an empire is to say that empires are states built on exploitation and disenfranchisement. Every empire must have someone who is ruled and dominated by their government, but sees no representation in it. The kingdom of France could (and did) have non-Frenchmen in it, but the Empire of France must do so. In every empire, there must be subjects, people whose political voices and rights are denied and whose wealth is extracted for the empire’s sake. The empires of Europe didn’t strive to make Africa richer: it was European cities which enjoyed development and improvement. An empire is an entity of injustice, without equality, and is most usually built and maintained by coercion and violence.

The Destruction of Jerusalem, part of the suppression of a Jewish rebellion which broke out after, in response to protests against over-taxation, the Romans plundered and looted the Second Temple. Source: World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/image/4032/the-siege-and-destruction-of-jerusalem/.

Think about the example in Life of Brian. What right did the city of Rome have to govern the people of Judea? The people of the region were taxed to finance projects in Rome or Italy, to fund armies fighting far off wars. Roman citizens were exempt from several taxes, but subjects in the provinces of the empire paid for citizen’s expenses. They were obliged to give what they had to Rome, and if they refused the legions would come and crush them. Of course, we might claim the Romans ‘gave back’, but did they really? Those roads the Romans built weren’t built for trade, they were made so the legions could get around quickly and crush dissent or rebellion. We credit empires for civic development as though the locals could never have done it themselves, and we ignore the question: did the people even want all this? Did they ask for the infrastructure or the institutions that Rome brought, or were they happy with their own? What right did Rome have to impose their systems on people around the mediterranean? The people of Judea were monotheists, and the Roman Empire expected them to venerate the empire as a God. Is that coercion progress? Was it ‘civilisation’ when Rome crushed Judean rebellions, killing thousands and destroying cities?

This idea that the empire brought ‘civilisation’ has so often been trotted out to justify conquest, oppression, and atrocity. Every empire does this, because they are at their core unjust entities whose growth and success always comes at the subjugation of someone else. How did Rome finance all its civic development and infrastructure? With slaves and wars. How did Britain finance the inventions and fleets of its empire? By ripping wealth from the colonies. How did the Aztecs keep find sacrifices for the altar? Through invasions and raids. Europeans claimed they were carrying progress and development to Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, but what they really brought was systemic violence and wealth extraction. Empires always claim to bring law and order, to create peace, but as Tacitus wrote, their peace is a desert, a political wasteland where every challenge to the empire’s power is silenced.

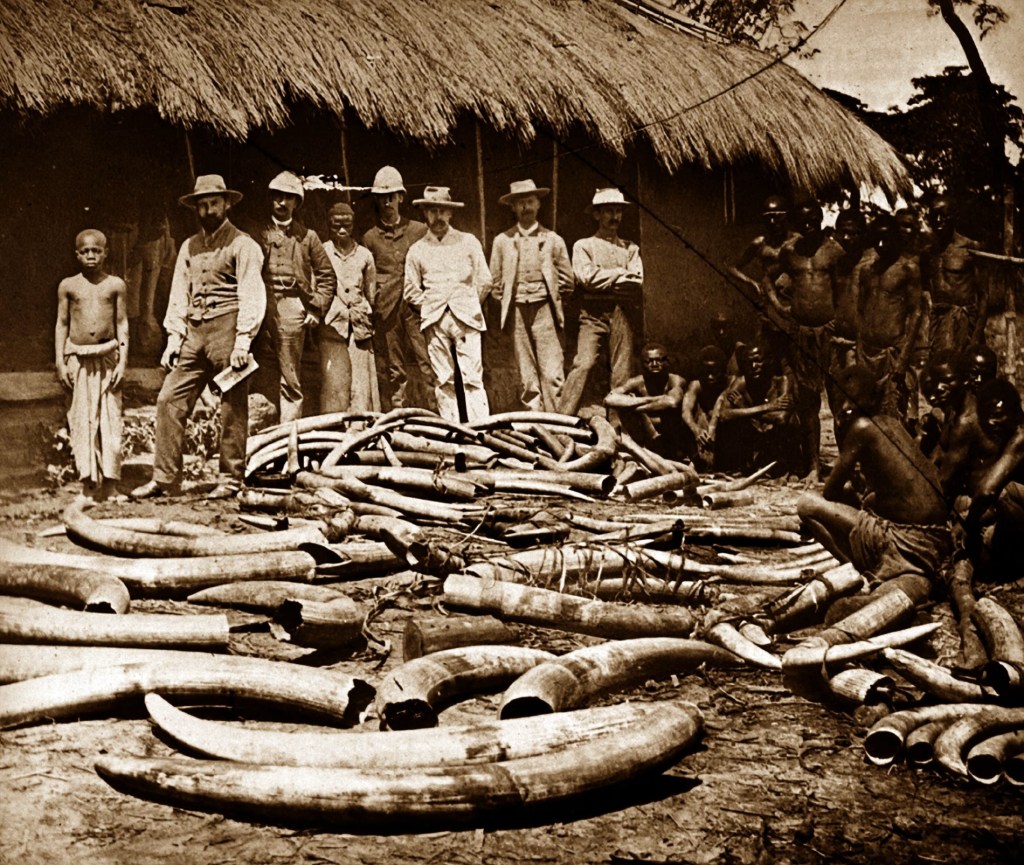

In Belgian Congo, up to ten million were killed by the colonial regime as it extracted wealth to build palaces and museums back home. This is the ‘peace’ and ‘civilisation’ of empires. Source: Jennifer Rankin, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/dec/09/belgium-addresses-postwar-apartheid-in-colonial-congo.

We have to remind ourselves that there are no ‘good empires,’ because the centres of media and culture are also places of imperial history and authority: places like the United States, or the U.K. Other historical empires, like Spain or Germany or Russia, might get portrayed as evil, but in the US and UK people are not as good at recognising their own empire’s injustice. There are still empires today, though they rarely acknowledge the title anymore, understanding the poor impression it makes. But make no mistake, an empire is an empire even if they dress up as a healthy democracy and insist they believe in freedom and human rights. In every empire, someone is being exploited and disenfranchised – if you don’t spot them, that’s only because they’re hidden out of sight, or your used to overlooking them. People sometimes venerate the grand European empires of old like Rome and Britain, but they shouldn’t. Those entities were built off injustice and violence, and are absolutely not things to return to. The only way we can have a world of progress, of equity and justice and respect, is if we disband the empires and never bring them back. There are no good empires, and every empire is an obstacle to progress.

Leave a comment